For a little over 2 years I’ve been supporting an internal learning program for my colleague Pete Cranston of Euforic Services. As we wrap up this project on “Learning about learning” in an international development context, Pete and I have debriefed and he is writing a series of comprehensive blog posts on our reflections. I want to pick up on one particular aspect of our conversation that struck me through the work, and which has also come up in a number of other contexts: the role of others in our learning. How does otherness help us learn? (Dr Zuleyka Zevallos, thanks for your great resource site on otherness!)

For a little over 2 years I’ve been supporting an internal learning program for my colleague Pete Cranston of Euforic Services. As we wrap up this project on “Learning about learning” in an international development context, Pete and I have debriefed and he is writing a series of comprehensive blog posts on our reflections. I want to pick up on one particular aspect of our conversation that struck me through the work, and which has also come up in a number of other contexts: the role of others in our learning. How does otherness help us learn? (Dr Zuleyka Zevallos, thanks for your great resource site on otherness!)

What we observed

Instead of starting with defining otherness, I want to share my experience. One important way to learn is with and from others. This is particularly relevant in workplace learning. In international development, regardless of the domain (agriculture, health, water/sanitation/hygiene, etc.) each investment of money, time and practice holds the potential for useful learning – useful to those implementing the work themselves, and to others interested in the same work. Often these lessons get stuck locally, or even remain invisible or unconscious because they don’t get a chance to be examined by ourselves or others. It is no surprise that many find a stark lack of reflection time, alone or with others. We learn through reflection, conversation, and the modeling and mentorship of others.

Our hypothesis in the learning to learn project (LAL for the acronym lovers out there) was that simply by creating more space and opportunity for conversational interaction between project staff, new insights would emerge and existing insights would gain wider visibility and application. We had a particular emphasis on conversational practice, both face to face and online. Learning with and from each other. While there was no explicit intention for mentorship, that possibility was always open.

Through the process, we noted the following three things that made a difference in conversational learning:

- Come out as a learner. Declare our intention and orientation towards learning by how we prioritize time and how we practice as learners. This includes being open about not knowing, willing to take learning risks (what, you don’t KNOW the answer!!!) and practice the art of asking questions and LISTENING to answers.

- Recognize what we are doing is reflective practice. We call it M&E (monitoring and evaluation), reviews, and all those business process words. It is more fundamental: Stop. Think. What did we actually learn? What do we know more about now? What new questions does that uncover? Unless we are intentional about our reflective practice, the learning drips by. Another way to view this is the idea of catching ourselves learning. Simply noticing triggers the potential and recognition of learning.

- Create space and leadership for learning. We can think about making it happens as about space. Or spaces. The fastest, but perhaps least rich is surveys. The shrink the time commitment and we know time is the biggest impediment. But what about actually making spaces for reflection? Can we commit 10 minutes in a weekly meeting? Something once a month? An annual learning review? We need to PUT that stuff in, notice when and how it becomes intentional. We must lead with it from from top by role modeling and recognizing reflection as a valid, yes, IMPORTANT use of our time. Yes, stuff t happens without leaders, but leaders make it happen better by lending legitimacy. We must lead from every direction and in every corner. Reflection and learning can be recognized by donors. Without being too literal, what about 10% for M&E, 10% for communications, and 10% for learning. That leaves 70% for the DOING and probably will increase the effectiveness and value of that doing.Don’t get me wrong. Learning is also random, chaotic, free flowing, emergent, and what we learn may often be different than what we set out to learn. The LAL project included very basic funded Learning Exchange Visits where grantees visited each others projects and went into the field. They had real time with each other and stuff just happened. The immersion triggers experiences and memories that take you conceptually to a new point. They can suggest new practices, behaviors and even ways of monitoring and evaluation. In the pursuit of learning with an open agenda, we embrace uncertainty and find new learning entry points.

Adam Frank writes about the Liberating Embrace of Uncertainty, which resonates with these three things Pete and I observed:

For science, embracing uncertainty means more than claiming “we don’t know now, but we will know in the future”. It means embracing the fuzzy boundaries of the very process of asking questions. It means embracing the frontiers of what explanations, for all their power, can do. It means understanding that a life of deepest inquiry requires all kinds of vehicles: from poetry to particle accelerators; from quiet reveries to abstract analysis.

So what about otherness?

When we discussed #3, I asked Pete, what did we notice about the culture of the organizations and individuals involved? We talked about the huge value of the leader’s openness, despite a position of positional and resource power (the funder!) We talked about the diversity of project staff – geographically, organizationally, amount of experience (age), etc. Then I was reminded about a question Bron Stuckey had recently asked on Facebook :

I am wondering how you would respond to the proposition “The best person to influence the practice of a novice is someone who was most recently a novice themselves” It’s some research bubbling up for which I have a real passion. I do have to admit it is more driven by intuition and first hand experience than a body of literature or prior research 🙂 Just wondering what my respected colleagues think of this proposition. Does it fit with your research, experience and vision?

The discussion that followed Bron’s question was diverse and fascinating. I’m sharing the thread, Bron Stuckey Learning With Others with her permission. Through it came the thread that learning happens in a (diverse) ecosystem of people, contexts and content and that who we learn with influences our learning.

The other we know and who knows us: Sometimes we learn best from people who’s experience is close to or just advanced of ours. It is a place of relative comfort.

The other we respect (and/or fear): Sometimes we learn from people with influence and power because that causes us to pay attention. Sometimes we learn from the deep experience of a expert or long-time practitioner.

The other we aren’t so sure about: Sometimes we learn from people who are different from us, hold different opinions and experiences because that asks us to examine our own understandings, biases and assumptions. This is a powerful but often more challenging set of others when we can step across mistrust and even animosity and step curiously into learning from someone who really is the “other” from us.

How otherness feeds into #1, #2, and #1

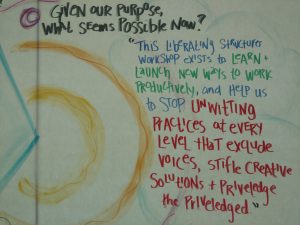

Coming out as a learner means we have to trust ourselves, regardless of the “others” we engage with. So part of our identity has to be “learner.” Reflective practice asks us to question our own assumptions, not just those of the “others.” And creating space for learning asks us to invite in the “others.” So for me, the bottom line is a strong look inward into identity, reflection and invitation. This requires us to stop our often unwitting exclusion of others, of not inviting, not listening and not engaging. Thus the opening picture. I bet you wondered why I picked it, right?

Stuff that Inspired this Post:

- Greg McVerry “When Networks Matter Most” https://medium.com/the-binder/when-networks-matter-most-e42077efbb77#.3x01ubytc and “In Search of Ikigai: Meaning Making as Culture” http://jgregorymcverry.com/in-search-of-ikigai-meaning-making-as-culture/

- Tony Bates, “Culture and Effective Online Learning Environments” http://www.tonybates.ca/2016/05/15/culture-and-effective-online-learning-environments/

- Nora Bateson’s concept of Symmathesy

Symmathesy = Learning together.(Pronounced: sym- math-a-see) A working definition of symmathesy might look like this:Symmathesy (Noun): An entity composed by contextual mutual learning through interaction. This process of interaction and mutual learning takes place in living entities at larger or smaller scales of symmathesy.Symmathesy (Verb): to interact within multiple variables to produce a mutual learning context….

The way in which we have culturally been trained to explain and study our world is laced with habits of thinking in terms of parts and wholes and the way they “work” together. The connotations of this systemic functional arrangement are mechanistic; which does not lend itself to an understanding of the messy contextual and mutual learning/evolution of the living world.

Reductionism lurks around every corner; mocking the complexity of the living world we are part of. It is not easy to maintain a discourse in which the topic of study is both in detail, and in context. The tendency is to draw categories, and to assign correlations between them. But an assigned correlation between a handful of “disciplinary” perspectives, as we often see—does not adequately represent the diversity of the learning fields within the context (s). The language of systems is built around describing chains of interaction. But when we consider a forest, a marriage, and a family, we can see that living entities such as these require another conceptual addition in their description: learning.

P.S. Added on Friday – Catherine mentioned an image in her comment below. Here is the image!

Nancy,

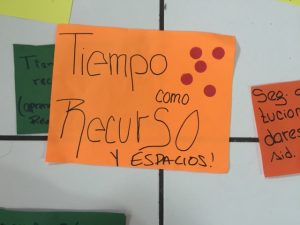

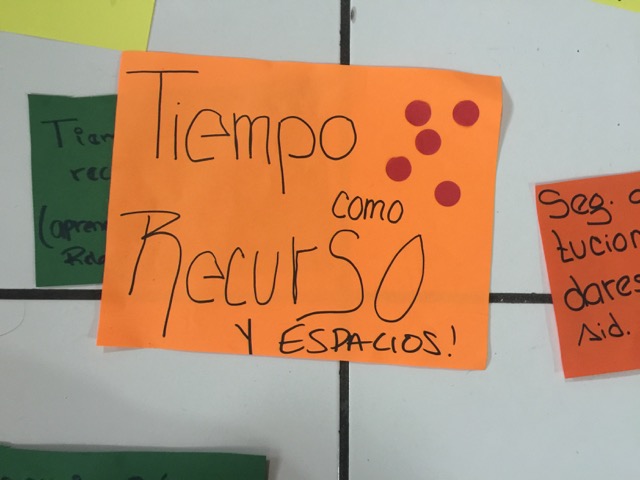

Thanks for this thoughtful post. Your points about creating the space for “reflective practice” are so critical. In a recent Theory of Change workshop we facilitated, the group came to consensus around a key need being “space and resources for reflection”. (I wish I could share the pic because it’s cool but can’t figure out how to…) I’m just writing a final report for a foundation we have been working with, and thinking about these same needs. I think one of the issues is that organizations always try to add this “reflective practice” on top of “business as usual” and therein lies the problem.They are still considering these top-down, highly contained practices as the core mode of operation, and the other stuff is just fluff really, so therefore it receives little prioritization. So, I’m thinking about how to encourage the reflective practice as a core strategy, and not an add-on.

Nancy Edit: here is the image:

Pete Cranston shared this on the KM4Dev list today and said I could share it here as an amplification:

Hi

The last couple of times we’ve done work with organisations around ‘failure’ we’ve used the term, ‘unanticipated outcomes’. The choice was partly to due with the word ‘failure’ and its associations, but also an attempt to balance the conversation, since a runaway success in a project or initiative is as interesting and powerful a learning opportunity as one where the outcome is labelled failure.

And importantly, I don’t think project staff can claim any more credit for something that was far more successful than envisaged than they have to take the blame for something that was seen to fail. In both cases all the people involved were unable to plan accurately, their assumptions and judgements were wrong, and management is ineffective. So the issue becomes one of exploring those assumptions and judgements, where they came from, what informed them and what can the people and organisation learn about how they do business. In both cases the issues are usually as much to do with systemic weakness and/or leadership deficiencies as they are to do with those caught in the storm.

A second point is that I think organisations and people learn a lot more often, and successfully, from situations where things are not going according to plan than they are given credit for. Investigating a large INGO, looking for good K&L practice, we found lots of instances where people had made changes as they went along, small ones, relating to, for example, project visits. Staff sit in vehicles going back home and have conversations about what they have seen, and often make decisions about what they will do differently following what they have seen. But the conversations aren’t captured, other than, for example, in a line in a later report that mentions a budget change, or a decision to find a new organisational partner. The actual learning from ‘failure’ happened almost incidentally. It’s classic ‘adaptive programming’, though it has only been called that recently! We used to call it ‘reflective practice’. It’s often triggered when there are ‘outsiders’ on the visit – from the organisation, or the funder, or another organisation: they ask unusual questions. Nancy White wrote an excellent blog summarising some of our conversations about how learning happens, how it is triggered in situations when change is necessary but there isn’t a huge incentive to do something or talk because the project or initiative is just bumbling along. It’s a great blog

http://fullcirc.com/wp/2016/06/09/embracing-uncertainty-diversity-and-othering-for-learning/

Finally, I think talking about failure is much more of an constraining issue when it becomes something more public, or with a higher profile. Once everyone is talking about it then of course people get defensive and things get buried. Keep it below the radar and things happen faster!

Cheers

Pete